Step 7: Find Your Raison d’Etre

Step 7: Find Your Raison d’Etre

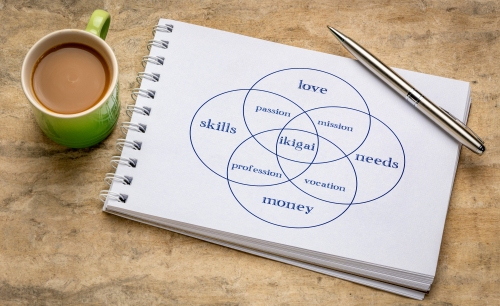

What do you consider to be your purpose in this world? Few people think about their life that way. In Japan, they call it your ikigai. In France, they refer to your raison d’etre. For Americans, that roughly translates to your purpose in life or your reason for being.

It’s easy to consider your family or even your career as your reason to live. But true embracement of the ikigai concept is more of a lifestyle, not a specific person, place or thing.

Your purpose may not even be something you’ve pursued in your adult life. Many of us follow the socially expected path: higher education, a good job, a rewarding career, marriage, home, and family. But those things are not everyone’s raison d’etre. They might wake up one morning thinking that once they’ve achieved all those goals, they will finally get the chance to do the one they’ve always wanted. What is that?

The older we get, the more we lose a spouse or life partner, siblings, or children – and those who retire no longer have work to feel fulfilled. As part of your retirement planning effort, consider life without any of those things. How would you bear it? If you outlive your career and loved ones, what would you do?

Note that your ikigai does not insulate you from bad things happening. Instead, it’s the thing you look forward to when the smoke clears: the light at the end of the tunnel. On balance, it’s the thing that helps get you through the pain and restores happiness. In fact, discovering your raison d’etre can help you better cope with stress and loss. People who pursue their ikigai tend to have better mental health, experience fewer chronic diseases, and are more likely to live longer.

Oftentimes ikigai is felt as part of a process. For example, the joy of mixing ingredients to prepare baked goods or a meal. Planting a garden. Rebuilding an engine. It can be the process of writing or painting or playing an instrument, but not necessarily finishing a novel or singing in public. It can be as simple as finding joy in daily activities, nurturing relationships or doing community service.

Another advantage to ikigai is that it can connect you with other people who share your passion, which can be very important as you grow older and more isolated. By leaning into your ikigai, you could expand your social network with connections that are meaningful and fulfilling.

For some people, their raison d’etre is spiritual. A belief and perhaps a greater connection to a higher being. They may wish to spend more time becoming involved in church activities, reading scripture that supports their religion, or even exploring other religions.

The Japanese culture believes that each individual has an inherent ikigai based on their personal values and beliefs. One way to think about it is as your philosophy on life. Since this step is a part of retirement planning, it is fortunate that you have lived long enough to have developed some philosophies on life.

For example, some people discover that family does not just consist of blood relatives. Instead, their concept of family is people who are there through good and bad times, who always show love and respect, who you can rely on. Those things might not always be true among family members who meet the traditional definition. This type of ikigai may help you recognize that the death of loved ones does not necessarily mean you lose your family. You can always build and add to your family (e.g., neighbors and friends, fostering children or pets, big brother/big sister programs).

How Do You Find Your Ikigai??

Many times, the hustle and bustle of life keeps us from finding our true purpose. We proceed as loyal soldiers down a path prescribed by society instead of pursuing things that may bring us greater happiness. There’s nothing wrong with a career and family, but there is likely something more that each of us can pursue that is personal and soul-enriching. Sometimes, you can discover your raison d’etre by exploring your passions, values, strengths, and skills. For example, ask yourself the following questions:

- When I was a child, I loved doing…

- If money didn’t matter, I would be…

- If I believed I could not fail, I would…

- I completely lose track of time when I am…

- I am most happy with who I am when I…

- I am really good at…

- If I didn’t care what others thought, I would…

- In my free time, I love to…

- If I had only six months to live, I would spend my time…

- If I were to die tomorrow, I would regret that I did not…

Consider hobbies or classes that you’ve always wanted to try or past experiences or achievements that gave you a sense of satisfaction and fulfillment. Recall where you have found inspiration in the past, and pinpoint what lies at the cross-section of doing what you love and doing what you’re good at.

Remember that your reason for living is more of a journey, not a destination. Finding your ikigai may take a lifetime to discover, so don’t be afraid to try out different pursuits. In fact, your reason for being may simply be to try new things.

Disclaimer ![]()